"I don't know whether I'm alive and dreaming or dead and remembering."

A young man is left nearly senseless, without eyes, ears, nose, mouth, arms or legs. Unable to perceive the difference between memory, dream and reality. His body lives on while his mind is trapped within it. This is the horrific situation that Joe Bonham lives in Johnny Got His Gun, the directorial debut of Academy Award and National Book Prize-winning author, screenwriter and member of the famous Hollywood Ten, Dalton Trumbo (Spartacus, Papillion, The Brave One, Roman Holiday).

Adapted from his own pre-World War 2 book Trumbo made this film during the height of the war in Vietnam. Joe is hit by an artillery shell while taking cover in a crater in the middle of No-Mans Land, and is left deformed. He is treated by surgeons who decree that he has been "de-cerebrated" and his madulla oblongata, which controls one's breathing, is the only part of his brain to survive. In their words, "he will be as unthinking and unfeeling as the Dead until the day he joins them." Joe later refers to himself as a "piece of meat that keeps on living." Joe soon wakes and slowly becomes aware of his state of being, he is beyond traumatised. As years pass, he constantly slips between memories of his childhood and life, dreams of what he can become in his present state, and fantasies wherein he speaks to his father, his lover Kareen and Jesus Christ about his predicament, all while slipping in and out of reality. Timothy Bottoms (Invaders from Mars, The Last Picture Show) plays Joe, Jason Robards (Once Upon a Time in the West, All the President's Men, Tora! Tora! Tora!) his father, Kathy Fields (The Towering Inferno) as his lover Kareen, and Donald Sutherland as Jesus Christ.

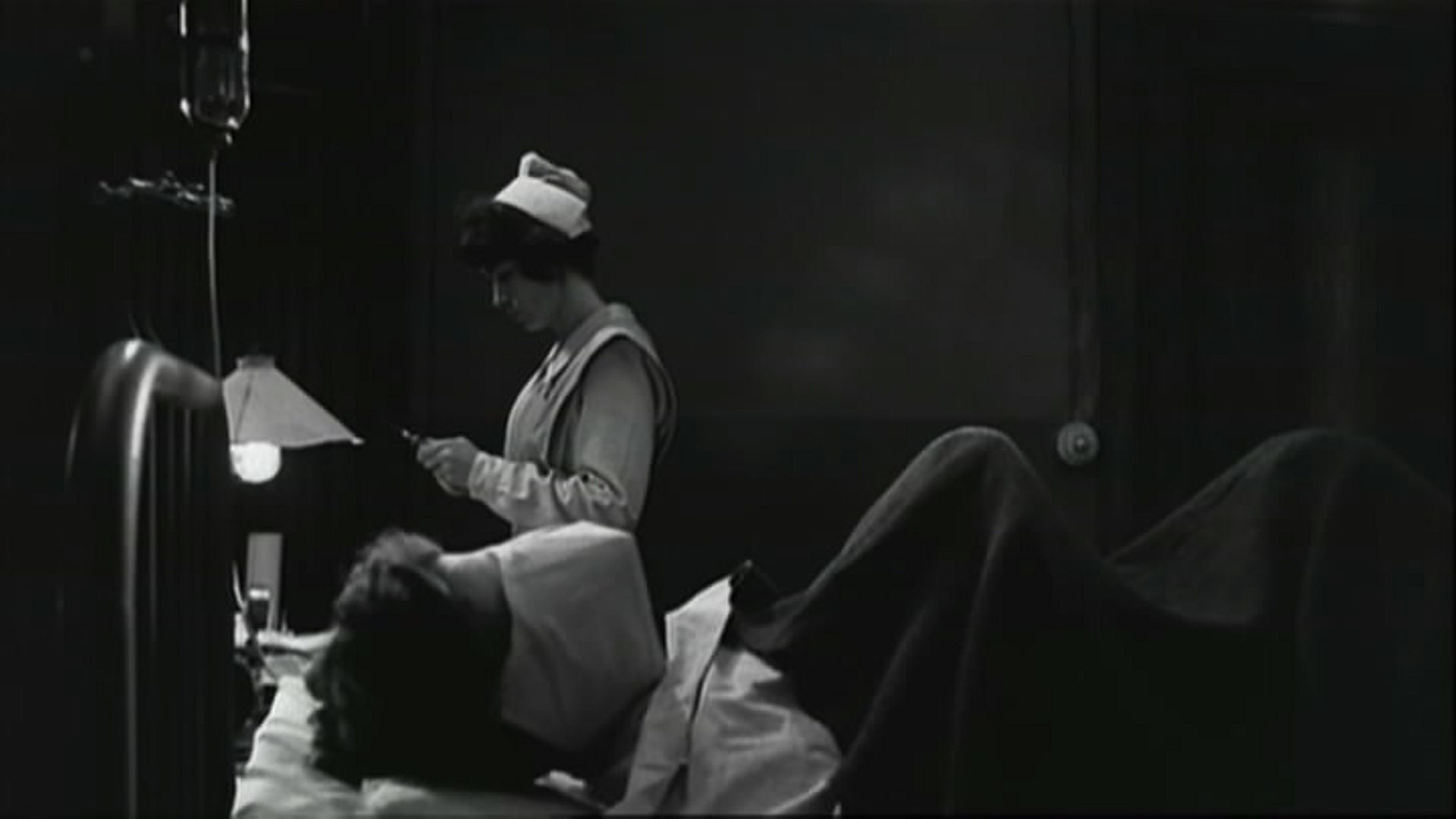

Uniquely, the film is split into two differing visual styles that it switches between, the black-and-white of the hospitalised and mangled Joe, and the colour-filled world of his memories and dreams. Though the latter does also appear saturated and at times employs a significant blur around the edge of screen. Within the Hospitalised Joe moments, his minds voice is often heard overlapping the dialogue that is happening outside of his mind, most notably in the early scene where he discovers having lost his legs while doctors discuss his injuries and treatment. The clinical discussion between doctors in the foreground of the shot dominates the screen space, but the bed-ridden Joe is completely visible in the background, and all the while he is screaming and moaning, and they are oblivious to each other. The doctors allow him to live in order to study, a conclusion Joe also makes with a fantasy involving a cameo from the director himself.

The film is rife with long, singular takes that emphasise intimacy and discomfort in a film already full of intense emotion, many of them between Joe and the near-mute nurse who takes tender care for him. These moments are tender and poignant, often being a more positive sadness to the films otherwise bleak hopelessness By direct contrast, there is one segment that shows how Joe comes to perceive time, where a years passes within a full minute of jump cuts and wildly different angles. This effort works in tandem with the hard cuts between dream and reality to create a sense of empathy between the audience and such an unimaginable situation. The editing of the films dreams and memory sequences allows for sound and image to bleed between opposing fantasies, and the film alternates between jump cuts and fades as it follows Joe's stream of consciousness. Sometimes the dreams come fast and obvious, other times more subtle, and the rat nightmare is a significant example of this. And further along, these get stranger and more surreal as Joe begins a descent into madness.

Joe Bonham as a character is meant to embody the Everyman's Son and also Trumbo's own experiences growing up in the turn of the century. As the film and book are both dominantly anti-war texts, they also touch on the spirit of class-ism, pastoralism versus modernism, within that period of history. The Bonham's move from Colorado to LA being a significant part of that, and it is often and loudly remarked on by Joe's father. Joe revers his father immensely, and even turns to him as he does Christ to help him with his situation, and his father often discusses with Joe about such concepts as democracy and capitalism. Early on he states that "For democracy, any man would give up his only begotten son." The film's title is a response to a popular recruiting song that contained a refrain stating "Johnny, get your gun!" But on the subject of the politics of the film, Trumbo stated that " I've tended more to center on the young man, the soldier, and let you draw your own conclusions about the system that put him where he was." But it is impossible to deny the staunch anti-war stance the film takes.

Johnny Got His Gun is a uniquely terrifying film, whose premise and source material seemed difficult, almost impossible to adapt into a film. The decisions made in the area of direction and editing are brilliant, with the contrast between the world of reality and the mind being so deliberately contrasted, but often they still can melt into one another. The way the camera moves with the actors, stays in one space, cuts, or even doesn't cut, is just brilliant. Trumbo was known as a brilliant screenwriter, and he also holds Johnny as "...obviously the best thing I've ever done maybe the one good thing I've done..." While strange, the direction for the actors to portray their characters with often restrained emotions and some with an odd cadence actually intensifies the idea of these people being from another time. Perhaps that makes the content even more horrific. The score is often sparse, dark and military, though with brief moments of soaring orchestration.

Trumbo's own adaptation differs vastly from his own book, which was written as a stream of consciousness entirely from Joe's own perspective and without any of the hospital scenes from beyond Joe's perspective. Trumbo has stated before that he was even investigated by the FBI based on his ideas and the novel, which he refused to continue to publish during World War 2. The novel also went on to become a personal favourite of Ron Kovic, the man who was Born on the Fourth of July. Donald Sutherland, a prominent anti-war campaigner who wanted to "Free or Fuck the Army" around the time the film was made, also felt highly about Trumbo's novel.

The film does end on a horrifically sad note, though Trumbo uses the last frame before the credits to make a sobering and sarcastic comment about the results of war in the 20th Century. In bold red typewriter font it says "War Dead since 1920: Over 80,000,000 Missing or Injured Casualties since 1920: Over 150, 000, 000 Dulce Et Decorum Est Pro Patria Mori". The latin translates to "It is sweet and right to die for one's country" and was most famously used in the 20th Century in the poem by the same name by Wilfred Owen.

The rights to Johnny Got His Gun are now owned by the thrash metal giants Metallica after the book and film inspired their 1989 song One and clips from the film were used in the music video. The band purchased the rights to avoid having to constantly have to pay royalties for using the footage.

No comments:

Post a Comment